Giles was born above his father’s tobacco shop near the Angel, Islington, London, on 29 September 1916. A pupil at Barnsbury Park School until the age of fourteen, he first worked as a stable lad before trying his hand as a pavement artist in Brighton. At the Wardour Street Film Company, he was soon promoted from office boy to animator and, as a consequence, moved to Elstree to join the studio of Alexander Korda (1930-35).

Giles was one of the principal animators of The Fox Hunt, the first British animated cartoon with colour and sound, which was produced by Korda and drawn by Anthony Gross. He then went to Ipswich, Suffolk, where he led the project to animate Ronald Davies’ popular Sunday Express strip, ‘Come on Steve’ (1936).

Giles returned to London to work for the left-wing Reynolds News (1937-43), producing a large number of drawings in each issue, including political cartoons and a strip, ‘Young Ernie’. During this period, his work revealed the influence of Pont, although his earliest colour work for the wartime joke books, Humours of the ARP and Laughs with the Home Guard, already prefigured the cover designs of the famous post-war annuals.

In 1943 Lord Beaverbrook persuaded Giles to join Express Newspapers as a war correspondent and as deputy cartoonist to Sidney Strube. Already the employer of Low and Vicky, Beaverbrook wanted the best cartoonists regardless of politics, and allowed them to convey an independent viewpoint. So Giles remained a Socialist throughout his life, and an ardent supporter of the trade union movement, yet Beaverbrook could call him ‘a man of genius’. John Gordon, editor of the Sunday Express, agreed that Giles could undertake an unpunishing schedule of two cartoons a week for the Daily Express and one for the Sunday Express, so allowing him to work from his farmhouse at Wittlesham, near Ipswich. Although he went to parties and occasional evenings in Fleet Street taverns, he kept out of the office and thus out of office politics. As a result, he stayed with Express Newspapers for more than fifty years, a record matched only by Tenniel and Shepard with Punch.

Initially Giles was employed to ridicule the Axis dictators as a war correspondent attached to the 2nd Army, with which he served in France, Belgium, Holland and Germany. He also produced animated films for the Ministry of Information, including The Grenade (1944), and had his cartoons reproduced as posters for such bodies as the Railway Executive Committee. Giles tried to depict the war, and all later events, from the viewpoint of the ordinary man in the street. Because of that stance, Simon Heneage has called him ‘the first social cartoonist to have a truly national appeal’ (‘Obituary’, Independent, 29 August 1995). Privately, his visit to the concentration camp of Belsen in 1945 may have transformed him into a ‘Christian Socialist’, but publicly he depicted the landmarks of history obliquely, by way of an earthy comédie humaine.

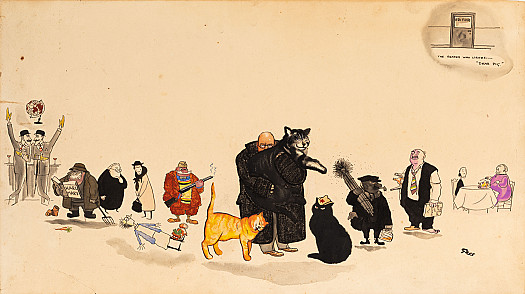

On 5 August 1945, Giles introduced into a cartoon what would become known as members of his immortal ‘Family’. This was a lower middle-class family, comprising a work-shy father, a sensible mother, their son George and his thin, sad wife Vera, and a number of children, including the diabolic Eric and the Twins. Over these ruled Grandma, described by Keith Mackenzie as a ‘bleakly menacing figure drawn from [the] dark subconscious, bird in hat, umbrella in hand and reeking of bombazine’ (quoted in Bryant 2000, page 90). The regular depiction of the anarchic affairs of these characters in the Express, and collected in the highly popular annuals, established Giles as a household name and had a great effect on British culture. Through his family, Giles influenced the style and subject of many cartoonists and inspired such radio and televisual characters as the Huggetts, the Glums, the Garnetts and the Ogdens. Giles’s Family itself appeared on television in animated advertisements for Tetley’s Quick Brew Tea.

The unique achievement of Giles was acknowledged in several ways. He received an OBE (1959), a Special Award for Distinguished Services to Cartooning (Cartoonists’ Club of Great Britain 1962) and an award from Granada Television’s What the Papers Say. He was also elected President of the British Cartoonists’ Association. Nevertheless, he parted company with Express Newspapers in October 1989 because he felt unappreciated – an underling having mentioned to him that the editor, Nick Lloyd, was no fan of his work. The swift response of the artistic community was to make him a senior fellow of the Royal College of Art. He was again much lauded following his death on 27 August 1995.

His work is represented in the collections of The Cartoon Museum. His archive is held by the British Cartoon Archive, University of Kent (Canterbury).