the right moment, has made him a world famous photographer.

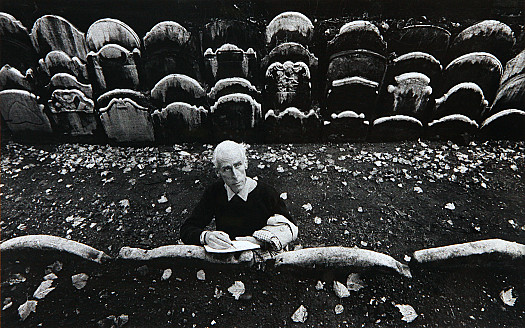

Despite this well-honed, well-known technique he has no recognisable photographic style, and indeed for the last half-century has made efforts to avoid developing one. He feels that as a photographer his role is to become an invisible observer, coaxing the truth out of his subjects without turning the result into a ‘Snowdon’.

Sifting through the thousands of photographs that we reduced to this representative selection in the catalogue, it became clear just how very different his work can appear as a result. He is a master of studio portraiture, photo-journalism, theatre, fashion, advertising, travel, nature and even underwater photography. His versatility is enormous; the ultimate photographic polymath.

Antony Armstrong-Jones was born in 1930, and seemed destined for a career in the arts; it was in his blood after all. His great-grandfather was the Punch cartoonist and photographer Linley Sambourne (1845-1910), and his uncle was the legendary theatre, ballet and opera designer Oliver Messel (1904-1978). Indeed, his prep-school headmaster guessed that academia was not his thing reporting; ‘Armstrong–Jones may be good at something, but it’s nothing that we teach here.’

His first forays into photography were at Eton, where he revived the Photographic Society and at Cambridge where he was a regular contributor to the Varsity magazine. Armstrong-Jones moved to London and after two apprenticeships, opened his own studio in a converted ironmonger’s shop in 1952. From this Pimlico base he began to forge the beginnings of a reputation. His pictures were being featured in Tatler and he got his first spread in the Picture Post; flamenco dancers at an Oliver Messel party. He also began to photograph the theatre, starting with the 1954 production of Terence Rattigan’s Separate Tables. The approach that he took was unheard of at the time, and was soon to establish his name. Disregarding the tradition for highly organised, posed pieces taken with large format, plate cameras, he chose to use a miniature camera to get amongst the actors backstage and during rehearsal, in an attempt to capture the essence of the play. The best results of this technique are badly lit, grainy, blurred and unusually composed. They deliberately reject traditional photographic values, brim with atmosphere, and embody the rebellious, vigorous energy that swept through British theatre in the 1950s. A picture in this style of Alec Guinness taken during a rehearsal of Hotel Paradiso first caught the attention of theatreland, and Armstrong-Jones was thereafter the photographer of choice for actors, directors and producers at this radically exciting time.

By 1956 he was already branching out beyond portraiture and theatre, working on advertising and fashion shoots for Tatler, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Daily Express, and beginning to research a book that was to be called simply, London. This was published in 1958 by Weidenfeld and Nicholson, and is a portrait of a city that takes the reader from seedy strip joints in Canning Town to The Chelsea Flower Show and The Trooping of the Colour. His pictures concentrate on the people of London rather than the buildings, and illustrate his interest in human interplay, reactions and expressions over formal composition and polish. His strong journalistic bent, so relied upon by newspapers in the decades to come, is obvious. London began a list of books now twenty two strong, the latest being of India, published in Autumn 2006 by the Khemka Foundation.

Armstrong-Jones’ marriage to Princess Margaret in 1960 slowed down his so far meteoric photographic career. Following the birth of their son, David, in 1960, he was created 1st Earl of Snowdon and spent much of his time performing royal duties. However, he still made time to do shoots for The Sunday Times colour supplement. In 1962 for example, he embarked on a series of touching pictures examining old age, finally published in 1965, the first of a number of commissions that dealt with social issues. He photographed a fourteen page article on British theatre in 1966 that coined the phrase ‘swinging London’, and he travelled to India, Japan and Italy for the magazine at various points during the decade. Although his photographic career slowed down, it gave him the freedom to indulge in other creative pursuits. From 1960 to 1965 he was commissioned to design a new aviary for London Zoo. The project, now a grade II listed building, took five years to complete and remains one of Snowdon’s proudest achievements. He won two Emmys for a television documentary, Don’t Count the Candles in 1968, and was also made responsible for the overall design of the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969.

By 1970 he was back working for Vogue, back working at the level of intensity that suited his drive, and was one of the most in-demand photographers in the country. His output from the decade is huge; he made six television documentaries, published seven books of his own work, held exhibitions in Cologne, London, the Far East, and Australia, whilst all the time contributing to the publications he helped define. This tireless attitude to work has continued to the present day. Now aged seventy six he has problems walking due to boyhood polio, but still holds regular shoots at the remarkably small and unpretentious home studio in which many of his photographs were taken, most recently the 80th birthday portrait of the Queen. The National Portrait Gallery, which holds one hundred and seventeen of his pictures, held a retrospective show in 2000 that toured to Edinburgh, Vienna, Moscow and the Yale Centre for British Art in the United States.