The life of the Russian-born artist, Paul Mak, was so crowded with incident that his biography reads like a novel. He was at various times an outstanding tango dancer, distinguished soldier, reckless gambler, impoverished labourer and enforced worker, first in a coal mine and then on an airfield. The stage for these activities took in not only Moscow and St Petersburg, but also Persia and Egypt, and several European capitals. Indeed, if he were not so divinely talented, there might be the danger of his life overshadowing his art. However, he distinguished himself in many forms of image-making, including portraits and caricatures, designs for the theatre, illustrations and Persian style miniatures.

At the height of his fame, he became court painter to the Shah of Persia and had many international exhibitions.

Paul Mak was born Pavel Petrovich Ivanov in the Moscow region of Russia 66 on 16 July 1891. He was the son of a retired colonel, aged 55, and his much younger second wife. However, he always claimed that he was actually the fruit of a liaison between his mother and a prince, who was his godfather.

Possibly even before he ended his schooldays at the First Moscow Gymnasium, Pavel Ivanov came into contact with the artistic community of Moscow, through his elder brother, Viktor Petrovich Ivanov (1888-1952), who worked as a literary and theatre critic under the pseudonym ‘Viktor Iving’. The distinguished painter, Natalia Goncharova, produced a portrait of Pavel in 1910, and would become a friend.

Between 1911 and 1914, Pavel Ivanov produced caricatures of leading cultural figures for several magazines, including the Moscow publication, Rampa i zhizn’ (Footlights and Life), and the St Petersburg publications, Satirikon and Teatri iskusstvo (Theatre and Art). In this period, he began to make use of the pseudonym, ‘Paul Mak’, and ‘Mak’ became his definitive signature by 1915.

Between 1911 and 1915, he also designed productions for Mamontov and Artsybusheva’s Theatre of Miniatures, at 42 Mamonovsky Lane, Moscow, which specialised in presenting one-act plays and ballets. It is possibly through this theatre that he met the famous dancer, Elsa Krüger. Gaining a passion for the then highly fashionable tango, he partnered Elsa with great success. He also painted her portrait.

Around 1913, Ivanov spent ten months of formal studies in the school run by the artists, K F Yuon and I O Dudin (the first private painting and drawing school in Moscow). He also absorbed the influence of such artists as Edward Burne-Jones and Aubrey Beardsley, who were known in Russia through magazines, and especially Mir iskusstva (World of Art). In spring 1913, he contributed portraits to a group exhibition at La Galerie Lemercier, Moscow, alongside many other artists, including Natalia Goncharova.

Accounts differ as to the year in which Ivanov began to take an active part in the First World War. According to articles published in English in 1929, in Apollo and Asian Affairs, he volunteered for service soon after war broke out, and went to train at the First Konstantinovskoye Military School in Kiev in 1915. He was then commissioned as a lieutenant in the cavalry – possibly the Black Hussars – and, though wounded several times, remained at the front and received the Military Order of St Vladimir (1st class with swords).

However, Ivanov’s younger son and chief biographer, Dr Dimitri Dourdine-Mak, provides a different account. He states that Ivanov did not enter the military school in Kiev until 1916, and was then sent to the front as an officer in the 89th Belomorsk (White Sea) infantry regiment, becoming involved in the last great offensive against the Germans. Seriously wounded with a break to his right femur, he underwent an operation, which saved his leg, but left it some centimetres short. Having been promoted to the rank of captain, he was awarded the St George Cross (4th class).

When the Bolsheviks came to power in October 1917, Ivanov was lying severely wounded in a hospital. Some months later, while still on crutches, he was arrested and incarcerated in Butyrskaya prison. During his time there, he was allowed to draw, and made a sketch of the prison governor, which helped him to secure his rehabilitation. The governor – an illiterate peasant – is said to have exclaimed, ‘Your fame as an artist will more than balance any harm you can do to Russia as an Imperialist’ (‘The Art of Paul Mak’, Journal of the Central Asian Society, 1929, page 249).

In 1920-21, Ivanov worked as a stage designer at the newly founded Terevsat (Theatre of Revolutionary Satire), on a corner of Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street, in Moscow. However, in 1921, he fled south with his wife, Elena Kourbskaia. They made a long and perilous journey by horse and on foot, by way of Turkestan and Afghanistan, with Ivanov making sketches on the way to exchange for a night’s lodging or a meal. Arriving in northeast Persia (now known as Iran), they lived for a while in Mashhad, in Khorasan, but in 1922 settled in Tehran.

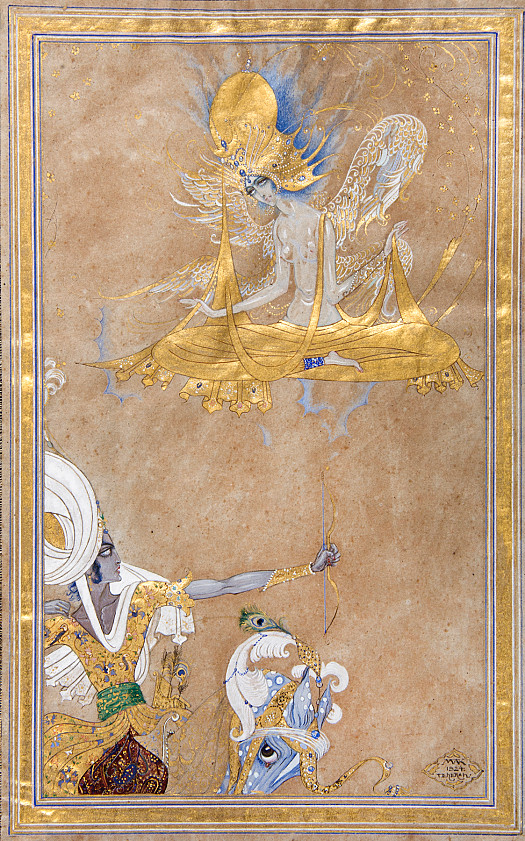

Initially, Ivanov trained the race horses of a rich dentist, frequented the races, painted and made amusing caricatures of the personalities that he met. Taking lessons from an old master of Persian miniatures, he acquired their technique and spirit. So he established a new style – exemplified by the works included here – and through it quickly developed popularity within high society. The friends he made included the Qajar prince, Mohammed Hossein Mirza Firouz, who had served in the Russian army during the First World War, and Friedrich-Werner, Graf von der Schulenburg, the German Ambassador to Persia.

In June 1925, an article with illustrations by Ivanov appeared in Asia: The Journal of the American Asiatic Association. This was ‘Ways of the Persian Heart and Mind: The Spectacle of Life Glimpsed Here and There in Streets and Gardens of Teheran’ by Thomas Pearson, the economic adviser to Persia. In the same year, his daughter, Elisabeth, was born in Tehran, and baptised there in the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint-Nicholas, her godfather being Graf von der Schulenburg. He and Elena also had a son named Wladimir.

At about this time, Sir Percy Loraine, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, introduced Ivanov to Reza Shah Pahlavi, the new leader of Persia. Having headed a British-supported coup in 1921, Reza Khan – as he was originally known – was selected Prime Minister in 1923, and became the first democratically elected monarch in 1925. He would do much to revive the arts in the country.

Early in 1926, Ivanov held a solo exhibition in Tehran, which included miniatures on themes from oriental history and literature and scenes from the everyday lives of Mongols, Turkomans and Persians. Later the same year, Ivanov commemorated the coronation of Reza Khan by painting a monumental full-length portrait of him. (It hung in the throne room of the Golestan Palace in Tehran, but disappeared following the overthrow of the imperial regime in 1979.)

In 1927, Ivanov was made official court painter, and, in the September, 68 became a Persian national under the name of ‘Mack’, a mistranscription of Mak. He seems not to have changed his citizenship again after this date. However, early in 1928, he left Persia for Egypt, where he earned his living painting portraits. He held an exhibition in Cairo in that year, and then others in London (‘Drawings in Colour’ at the Leicester Galleries in 1928), Paris (1928-29, both alone and with the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts) and again in Cairo (1930).

In 1929, a Georgian prince, Iveria Mikeladze, commissioned Ivanov to paint a portrait of Lord Allenby, Chairman of the Central Asian Society, and then presented it to the society.

In 1931, Ivanov moved to Athens, where he had previously settled his sister, Valentina. In the same year, he held an exhibition of his work in the city, at the gallery called Palais de Versailles.

In 1932, he moved to Paris and held an exhibition at the gallery, Bernheim- Jeune, in December of that year. From Paris he visited London to mount a second exhibition, ‘Persian Miniatures and Drawings’, which was held at the Fine Art Society in 1933.

Though making money from these international exhibitions, he lost much of it while gambling on horse races in each of the cities.

In 1938, he was forced to leave France by the Paris Prefecture, as a result of pressure from the influential Armenian oilman and philanthropist, Calouste Gulbenkian. This was because Gulbenkian believed that Ivanov had become the object of affection of his married daughter, Rita. She was married to Turkish born, Kevork Loris Essayan, who worked closely with Gulbenkian in the fields of finance, oil and diplomatic affairs.

In March 1938, Ivanov moved to Belgium, living first to the south of Namur and then, from the May, in Brussels, which provided a home to many émigré Russians. There he produced miniatures for exhibitions that did not materialise and attempted to gain commissions for portraits. By March 1939, his circumstances were so desperate that he was forced to work as a labourer, painting the interiors of shops, producing lettering on their windows, and even engaging in plastering. In February 1940, the government decision ‘to regularise the situation of immigrants with no income’ led him to become a coal miner in the region of Charleroi. However, following the Nazi invasion of the country in May 1940, he was forced to work at the airfield at Evere, on the eastern edge of Brussels.

In 1942, Ivanov met Lydia Dourdina, a young actress of Russian origin, who had worked at the Universum Film AG in Berlin before the war. She wrote to Graf von der Schulenburg, who led the Russia Committee of the German Foreign Office, to explain Ivanov’s position, and as a result he was released from his forced labour and able to return to painting. (In 1944, Schulenburg was implicated in a plot to assassinate Hitler, charged with high treason and executed.) Even before the end of the war, he began to exhibit again, contributing to the Salon des Peintres Russes at the Galerie de la Toison d’Or, Brussels (between 18 December 1943 and 5 January 1944).

Becoming Ivanov’s mistress, Lydia gave birth to his son – Dimitri Dourdine- Mak – in January 1946. However, during the course of 1945, he had already fallen in love with Emilie Mostovoy, who had two young children from her former marriage to Léon Wrangel. So, before Dimitri was of walking age, he left Lydia for Emilie.

For the last 20 years of his life, he lived and worked in the Brussels suburb of Ixelles, in a two-room, first floor apartment at 558 Chaussée de Waterloo. He exhibited his work regularly in Brussels, Charleroi, Ghent and Antwerp.

He died in Brussels on 22 June 1967, and was buried in the cemetery at Ixelles. Retrospective exhibitions took place in Belgium and England. The first was entitled ‘Exposition retrospective des oeuvres de feu Paul Mak’, and held at the Galerie Rubens in Brussels (between 31 October and 12 November 1967). The second was ‘Works of Paul Mak (1890-1967)’, which was organised by Mak’s elder son, Wladimir, and held at the Walton Gallery in London (in August 1968).

Further reading

‘The Art of Paul Mak’, Journal of the Central Asian Society, Vol XVI, 1929, pages 249-250; Dr Dimitri Dourdine-Mak, ‘Le Peintre Paul Mak’, on his website, dourdine-mak.be (in French); ‘Ivanoff P (alias Paul Mac)’, on the website, artrz.ru (in Russian)