Thomas Blakeley Mackenzie (1888-1944)

Thomas Mackenzie was one of the last of the major illustrators of gift books, those beautifully produced editions of classic tales of wonder. He knowingly absorbed the influences of such major predecessors as Aubrey Beardsley, Kay Nielsen and Harry Clarke in order to create his own style. Skilled as a printmaker as well as a draughtsman and watercolourist, he made use of linocut and etching in responding to some of his later commissions.

Thomas Mackenzie was born in Bradford, Yorkshire, the elder son of the wool combing overlooker, James Bates Mackenzie, and his wife, Nellie (née Blakeley). At the time of his birth, the family was living at 3 Upper Pollard Street, Bowling. He was educated at a local board school, and then probably at Belle Vue Secondary School (Boys).

It has been suggested that he began his close friendship with the future writer, J B Priestley (1894-1984), at Belle Vue. However, this is unlikely, given that Priestley arrived at the school in 1905, while Mackenzie finished his schooling in about 1903. By that time, he and his family had moved to 31 Balfour Street, and his father had established a wholesale business in bakery and confectionery.

Mackenzie was encouraged to develop his ability to draw by teachers at both his schools. However, his parents were apparently reluctant to let him pursue an artistic career. What happened next, and for the seven years of his life between the ages of 15 and 22, is not known. A story has circulated that he ran away to study in Munich, a significant artistic centre at the time. This has been accepted by Peter Cope (2011, page 9), but dismissed by Colin White (1988, page 11), who suggests instead that he undertook an apprenticeship (which conventionally took seven years), possibly as a draughtsman at a firm of engineers or printers.

At the time that Mackenzie entered Bradford School of Art in 1910, he and his family had moved to 443 Killinghall Road, and his father had become an insurance agent. While there, he met fellow student, Florence Mary Anderson, who, like him, would become an accomplished illustrator. In 1912, both he and she won scholarships for two years’ study in drawing and painting at the Slade School of Art, in London, under Henry Tonks. However, Mackenzie left after a year, possibly because of an aesthetic disagreement or because he decided to seek paid work. In the meantime, he and Anderson had become lovers, and she gave birth to a son, Murray Anderson Mackenzie (in Epsom, Surrey, in May 1914). Murray would be brought up mostly by his grandparents in Yorkshire.

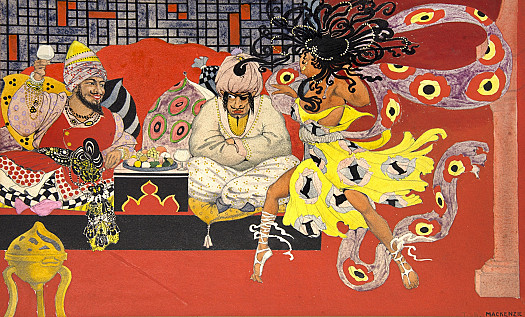

On leaving the Slade in 1913, Mackenzie went to the publisher and distributor, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co, and presented his portfolio, which contained drawings that showed the influence of Aubrey Beardsley and Harry Clarke. As a result of the visit, he received a commission to illustrate a small volume of Christmas carols, and this would eventually be published in 1916 (with the illustrations being credited to ‘T Mackenzie’). In the meantime, he made a somewhat uncertain living, mainly contributing drawings to The Sketch and other magazines. He also received an important commission from the publisher, James Nisbet, to illustrate Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp, a large new gift book with a rhyming text by Arthur Ransome. However, this project was temporarily abandoned as a result of the increasing scale of the world war. In a letter of 15 February 1915, Ransome complained that Mackenzie had ‘suddenly gone off to Serbia’ on active service.

At the end of the First World War, Mackenzie bought Old Rushes, a cottage in the Hertfordshire village of Rushden, and this would remain his bolt hole for years to come. In 1918, Harrap published his first significant book, Ali Baba and Aladdin, his name appearing on it as ‘T Blakeley Mackenzie’. In the following year, Nisbet finally published its version of Aladdin in both deluxe and trade editions in time for the Christmas market (the illustrator appearing simply as ‘Mackenzie’). It was well received by the critics, and proved influential, even on the design by William Cameron Menzies of the 1924 film, The Thief of Bagdad (over which Mackenzie would consider legal action). Nisbet followed Aladdin with Arthur and His Knights, solely in a trade edition (1920), Mackenzie illustrating a text by his friend and Nisbet’s juvenile book editor, Christine Chaundler. By 1921, he ‘was said to be the best paid illustrator in the country’ (White, 1988, page 27).

In the years immediately following the war, Mackenzie and Anderson ‘rented various properties in and around London as well as travelling between London and Yorkshire singly or together’, though ‘they seem to have grown apart’ (Cope, 2011, page 13). In 1921, while on a walking holiday in Yorkshire, he met Katharine Clayton, who had recently completed her studies in jewellery design at Birmingham School of Art. He and Clayton spent increasing amounts of time together, including a further visit to Yorkshire in 1923, during which he made preparatory drawings for the illustrations to his next book, for Bodley Head, which were executed in etching, linocut and watercolour. This was the non-fiction volume, Brontë Moors and Villages from Thornton to Haworth, by Elizabeth Southwart, whose work Anderson had also illustrated.

Mackenzie’s next two illustrative projects were more characteristic, in being gift books that showcased his talents for, respectively, the Orientalist and the fantastic. These were James Elroy Flecker’s play, Hassan (Heinemann, 1924), and James Stephens’ The Crock of Gold (Macmillan, 1926), the latter appearing in both deluxe and trade editions.

Perhaps responding to a boom in etching, Mackenzie worked increasingly as a printmaker, and exhibited etchings and engravings with the London dealer, Alex Reid & Lefèvre. It is therefore understandable that his last two books should be illustrated with forms of print, linocuts for F J Harvey Darton’s A Parcel of Kent (Nisbet, 1926), and drypoints for a two-volume limited edition of Walter Pater’s Marius the Epicurean (Macmillan, 1929, with an introduction by Mackenzie’s friend, the poet and critic, J C Squire).

In 1925, Mackenzie and Anderson had married at Hampstead Registry Office in order to make Murray legitimate. However, shortly afterwards, Anderson filed for divorce on the grounds of Mackenzie’s adultery. Cope explains that ‘It is on record that the presiding judge suspected collusion between the parties, but subsequent enquiries failed to substantiate his view’ (2011, page 14). The divorce was granted in October 1928.

In January 1929, Mackenzie married Katharine Clayton at Hampstead Registry Office. Soon after, they left for Paris, where Mackenzie hoped to fulfil a long-held dream of establishing himself as a painter. Inspired by the formal qualities of both Piero della Francesca and Cézanne, he had for some time been producing landscapes and still lifes. However, he did not succeed in his plan, and after six months they returned to live at his cottage in Rushden with their savings depleted. He then survived by contributing to magazines and selling topographical etchings to gift shops (including views of Oxford), while Katharine produced jewellery. In 1936, he exhibited at the Royal Academy for his one and only time; the work, entitled Tuning Up, was probably an etching.

In 1937, the Mackenzies moved to Cornwall, and settled in a stone cottage in Trewetha Lane, Trewetha, near Port Isaac. There they founded a summer school for paying students, which initially proved a success, but was forced to close following the outbreak of the Second World War. In the Register for 1939, Mackenzie described himself as ‘artist, designer, etcher, lithographer, visualiser’, and Katharine as ‘artist, jeweller, etcher’. They returned to making jewellery and, in his spare time, Mackenzie wrote detective novels; however, he thought none of them worthy of publication and requested that, following his death, they be destroyed.

Thomas Mackenzie died of lung cancer at home in Trewetha on 8 December 1944, at the age of 56. His ashes were scattered over Buckden Moor, Yorkshire, where he and Katharine had first met.

Further reading

Peter Cope, ‘Heart v Art: Florence Mary Anderson and Thomas Mackenzie’, Illustration, Spring 2011, pages 8-15;

Colin White, ‘Thomas Mackenzie and the Beardsley legacy’, Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Winter 1988, pages 6-35