Born in Edinburgh, Samuel Laing (1812-1897) was educated at St John’s College, Cambridge, graduating BA as second wrangler in 1831 and was elected a fellow of St John’s in 1834, remaining there for a period as a mathematical coach. He was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in November 1832 before being appointed private secretary to Henry Labouchere (afterward Lord Taunton), then president of the Board of Trade. He was appointed secretary of the newly formed railway department in 1842 and was a significant contributor to Gladstone’s Railway Act of 1844. In 1848 he was appointed chairman and managing director of the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway. He resigned in 1852, though the company struggled financially in his absence and he was persuaded to return in 1866, and he remained in charge of the company until his retirement in 1894. Following his initial resignation in 1852, he was returned as Liberal MP for Wick. He lost his seat in 1857 but was re-elected in 1859. In 1860, he served briefly as financial secretary to the Treasury before becoming financial minister to the crown in India, a post he held until 1865, when he returned again for Wick until 1868. At the time of his appearance in Vanity Fair, Laing had just been returned as MP for Orkney and Shetland, a post he held until 1885.

At the age of seventy and following his retirement from Parliament in 1885, Samuel Laing found further success in a new career as an author of accessible scientific and anthropological thought. His Modern Science and Modern Thought (1885) was widely read and was followed by A Modern Zoroastrian (1887), Problems of the Future, and other Essays (1889), The Antiquity of Man (1891) and Human Origins (1892).

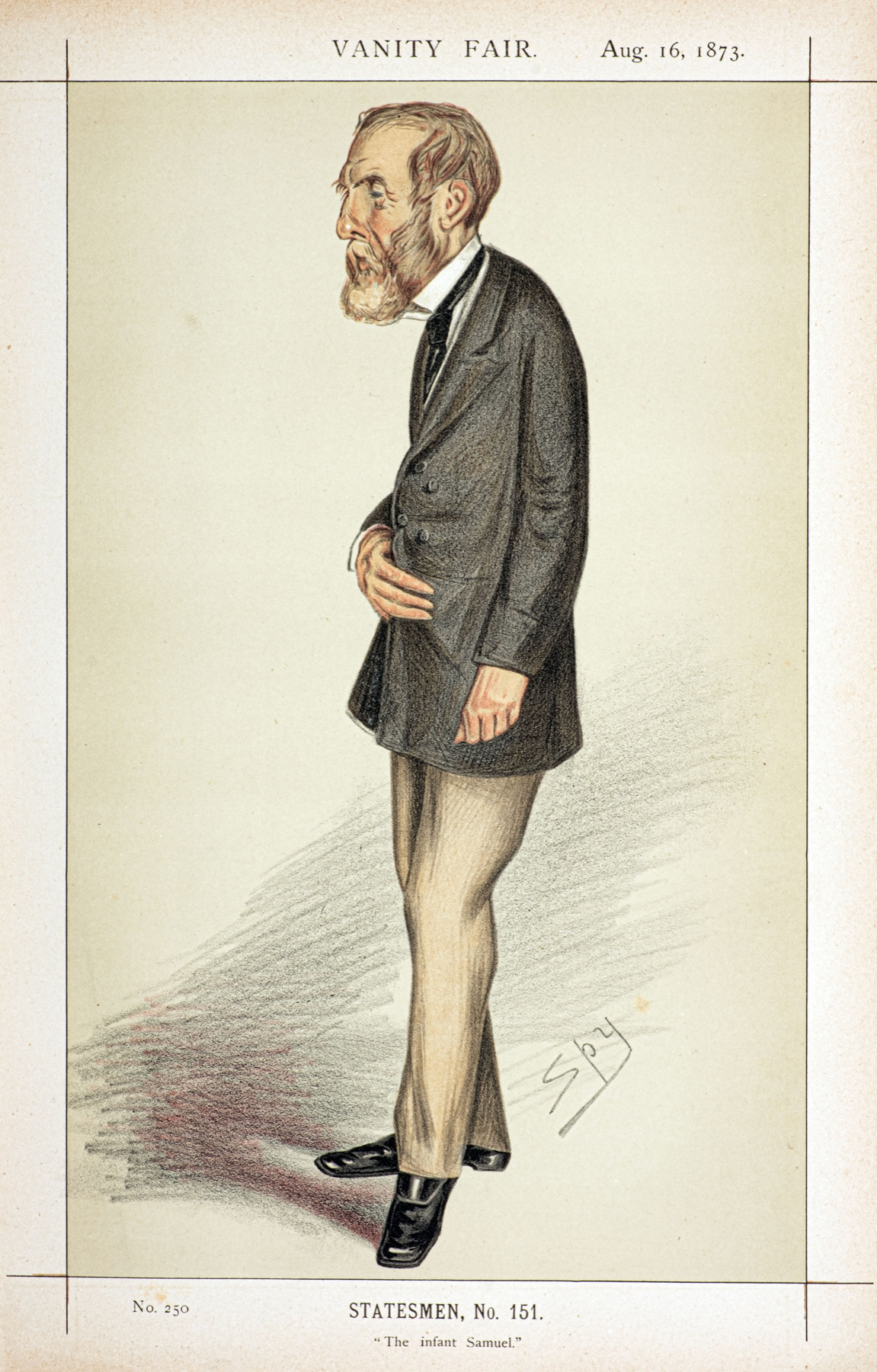

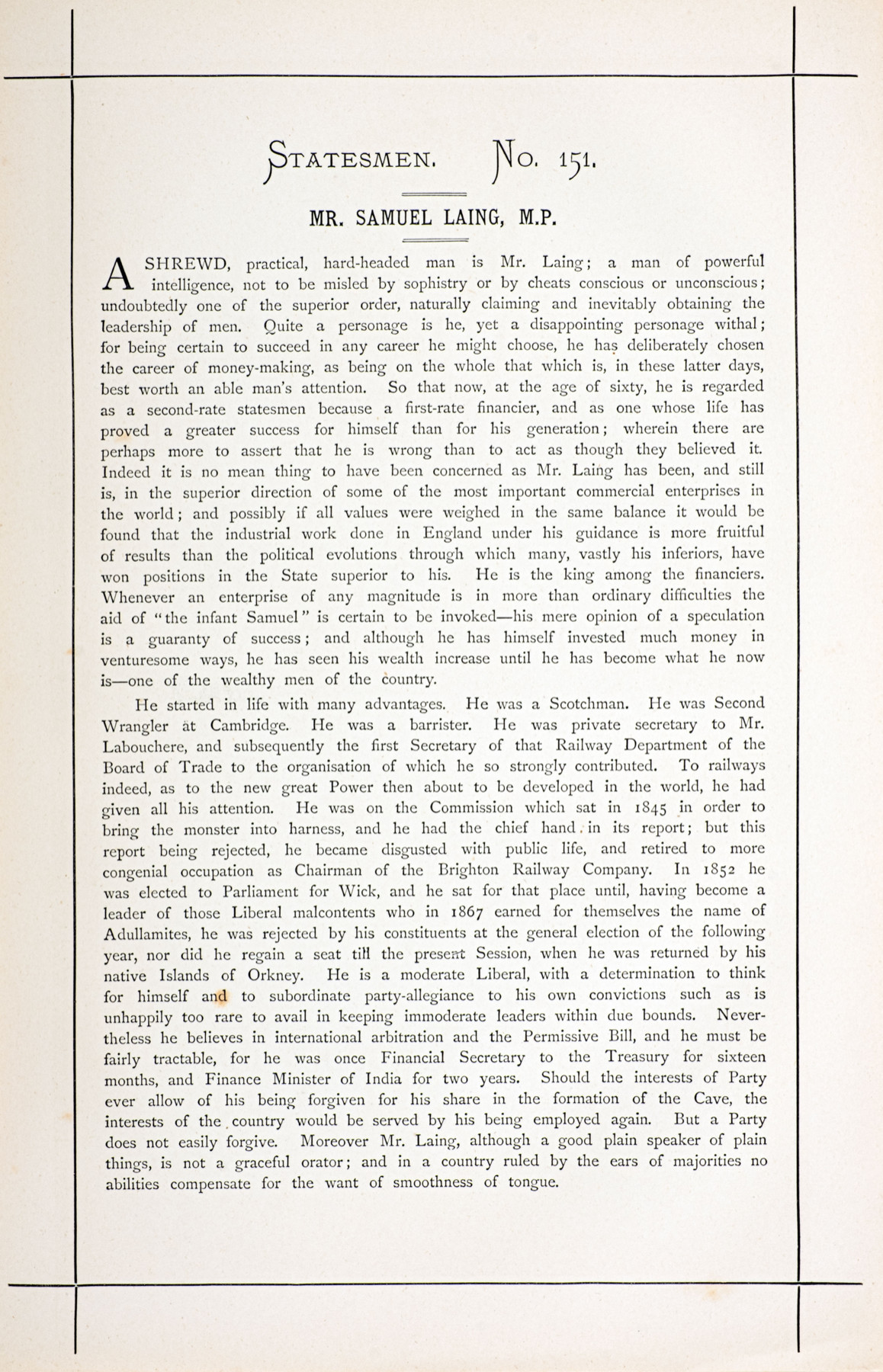

“A shrewd, practical, hard-headed man is Mr. Laing; a man of powerful intelligence, not to be misled by sophistry or by cheats conscious or unconscious: undoubtedly one of the superior order, naturally claiming and inevitably obtaining the leadership of men. Quite a personage is he, yet a disappointing personage withal; for being certain to succeed in any career he might choose, he has deliberately chosen the career of money-making, as being on the whole that which is, in these latter days, best worth an able man's attention. So that now, at the age of sixty, he is regarded as a second-rate statesmen because a first-rate financier, and as one whose life has proved a greater success for himself than for his generation; wherein there are perhaps more to assert that he is wrong than to act as though they believed it. Indeed it is no mean thing to have been concerned as Mr. Laing has been, and still is, in the superior direction of some of the most important commercial enterprises in the world; and possibly if all values were weighed in the same balance it would be found that the industrial work done in England under his guidance is more fruitful of results than the political evolutions through which many, vastly his inferiors, have won positions in the State superior to his. He is the king among the financiers. Whenever an enterprise of any magnitude is in more than ordinary difficulties the aid of ‘the infant Samuel’ is certain to be invoked - his mere opinion of a speculation is a guaranty of success; and although he has himself invested much money in venturesome ways, he has seen his wealth increase until he has become what he now is - one of the wealthy men of the country.

He started in life with many advantages. He was a Scotchman. He was Second Wrangler at Cambridge. He was a barrister. He was private secretary to Mr Labouchere, and subsequently the first Secretary of that Railway Department of the Board of Trade to the organisation of which he so strongly contributed. To railways indeed, as to the new great Power then about to be developed in the world, he had given all his attention. He was on the Commission which sat in 1845 in order to bring the monster into harness, and he had the chief hand in its report; but this report being rejected, he became disgusted with public life, and retired to more congenial occupation as Chairman of the Brighton Railway Company. In 1852 he was elected to Parliament for Wick, and he sat for that place until, having become a leader of those Liberal malcontents who in 1867 earned for themselves the name of Adullamites, he was rejected by his constituents at the general election of the following year, nor did he regain a seat till the present Session, when he was returned by his native Islands of Orkney. He is a moderate Liberal, with a determination to think for himself and to subordinate party-allegiance to his own convictions such as is unhappily too rare to avail in keeping immoderate leaders within due bounds. Nevertheless he believes in international arbitration and the Permissive Bill, and he must be fairly tractable, for he was once Financial Secretary to the Treasury for sixteen months, and Finance Minister of India for two years. Should the interests of Party ever allow of his being forgiven for his share in the formation of the Cave, the interests of the country would be served by his being employed again. But a Party does not easily forgive. Moreover Mr. Laing, although a good plain speaker of plain things, is not a graceful orator; and in a country ruled by the ears of majorities no abilities compensate for the want of smoothness of tongue.”

mounted