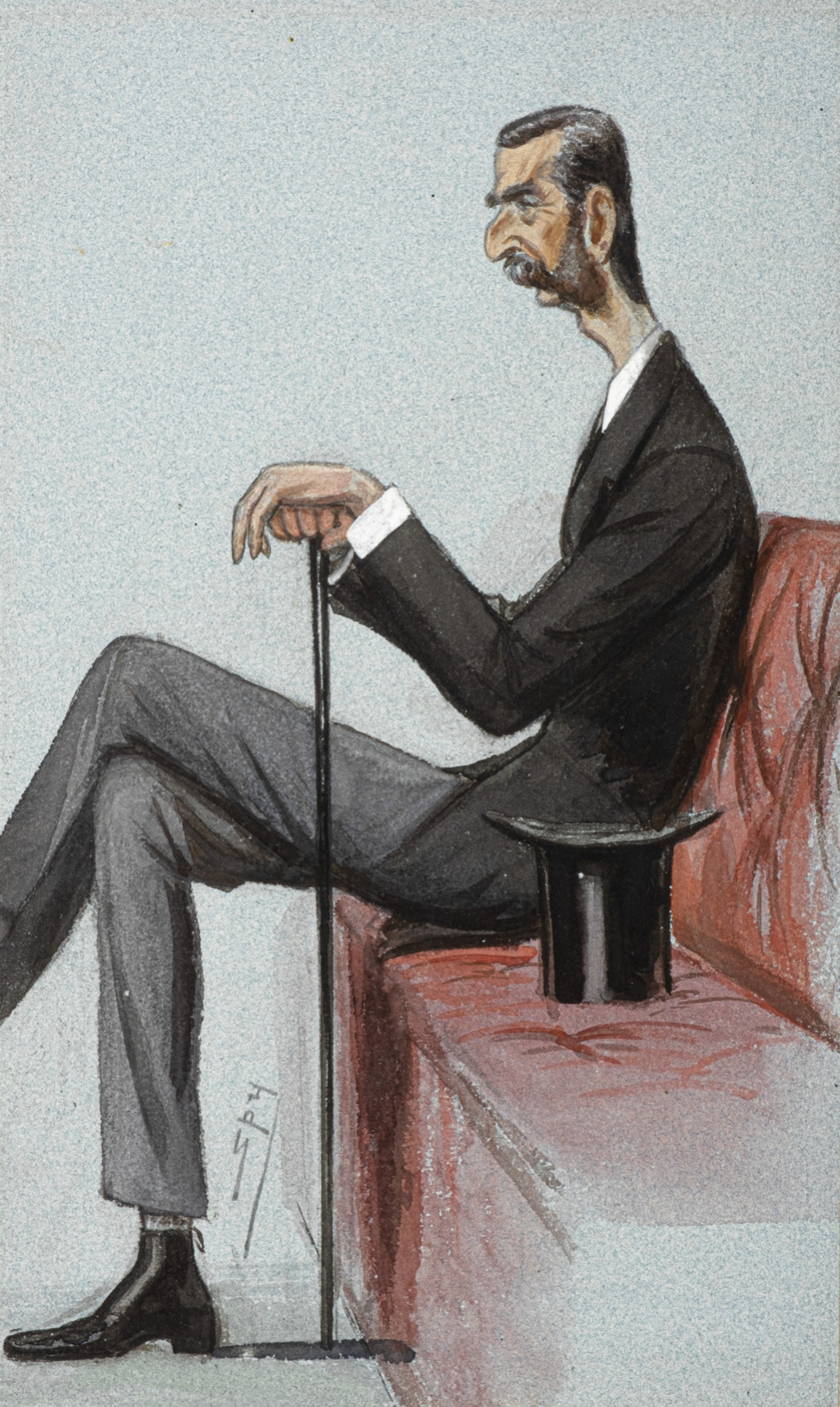

(click image to enlarge)

Frederic Augustus Thesiger (1827-1905) was an army officer who served for sixteen years in India before being made major-general in 1877. The following year he was selected as general officer in South Africa and charged with ending the Cape Frontier War. Under his command, the British forces were defeated at the Battle of Isandlwana (also known as Isandula), for which Chelmsford suffered strong criticism back in Britain.

“Some generations ago a German named Thesiger came from Saxony to England and married an Englishwoman. Then Thesigers began to determine to the Customs, the Army, and the Navy. Finally, Frederick Thesiger went into Law and Conservatism, got made Attorney-General by Sir Robert Peel, and in due course of time became Lord Chancellor and Baron Chelmsford. But the Baron outlived the reputation of the Attorney-General, and when he was verging towards four-score he was set aside by the Conservative leaders for the younger Lord Cairns. The result was that the Thesiger family was held to have acquired, from the passing over of its head, a special claim to be ‘got on.’

The present and second Baron Chelmsford was at that time the eldest son and heir-apparent of the ex-Chancellor. He was in the Army, and he became an object of special interest to the Commander-in-Chief and the rest of the Royal Family. In 1867 he was sent with Lord Napier as Deputy-Adjutant-General to Abyssinia, where he exerted himself more successfully in suggesting his own idea of his own importance than in establishing a reputation for accuracy. But he still grew in favour with the Court and the Horse Guards. He became distinguished as an able player of Kriegspiel. He was appointed Aide-de-camp to the Queen. He was installed in the command of an infantry brigade at Aldershot, and when in 1878 things began to look serious in South Africa he was sent out to the Cape as Commander-in-Chief and Lieutenant-Governor. In October, 1878, finding that he would probably be ordered to invade Zululand, he carefully inspected the borders of that country, and in November he reported that in a few weeks he should be ready to enter it. Accordingly he did enter it in January, 1879, and encamped at Isandula. On the 22nd January, hearing that the enemy had been found, he left his camp in the charge of Colonel Pulleine, with orders to ‘defend it,’ but without having either ascertained whether there was any special danger to it, or having given any specific orders to meet such a danger. He had scarcely got well away from the camp before - at nine in the morning - he received a note from Colonel Pulleine announcing that fighting was going on hard by the camp. He sent an officer to the top of a hill with a telescope, and ‘having no cause to feel any anxiety about the safety of the camp,’ wandered on, looking into dongas and ditches for the Zulus. Meantime the Zulus had fallen upon his camp in overwhelming numbers, and had massacred nearly every soul therein, to the number of over fourteen hundred men. When Lord Chelmsford returned in the evening from his wanderings he found a shambles instead of a camp. He was horror-stricken and panic-stricken. He scuttled away with the remains of his army before it was light the next morning, and without waiting to see if by chance any of the devoted defenders of the camp yet remained alive. Having got to a safe distance, he wrote a despatch declaring the disaster to be ‘to me almost incomprehensible,’ and conveying that it arose through the men not having had the courage to ‘keep their faces to the enemy.’

Upon the first news of Isandula arriving in England the Queen sent a precipitate telegram to Lord Chelmsford expressive of condolence and confidence. This was as unfortunate as it was premature; for it has been made abundantly clear by Lord Chelmsford's own despatches that he was not wholly entitled to confidence, and that the condolence should have been reserved for those who were committed to his leadership. The great player of Kriegspiel having been outwitted, out-manœuvred, and beaten in strategy and in tactics by ignorant savages, began to whimper. He complained of ‘the strain of prolonged anxiety and exertion, physical and mental.’ In the involved and floundering language of a distraught man he begged to be relieved of that strain. All too tardily, and after having been allowed an entirely insufficient chance to whitewash himself by being present at the Battle of Ulundi, he was so relieved, and returned to England to be caressed by the Court and the Horse Guards, and to assume the position of a General who had suffered the most disgraceful defeat, in British annals.

Lord Chelmsford is not a bad man. He is industrious and conscientious so far as his lights guide him, But Nature has refused to him the qualities of a great captain. He has suffered much and is entitled to a certain commiseration. But he has been ill-served by Fate and his friends; and he has not yet understood that the duty of a General who has sacrificed an army and has yet escaped the fate of Byng, and even a trial by court-martial, is to avoid the public gaze. For he is still ready to return thanks for the Army.”