(click image to enlarge)

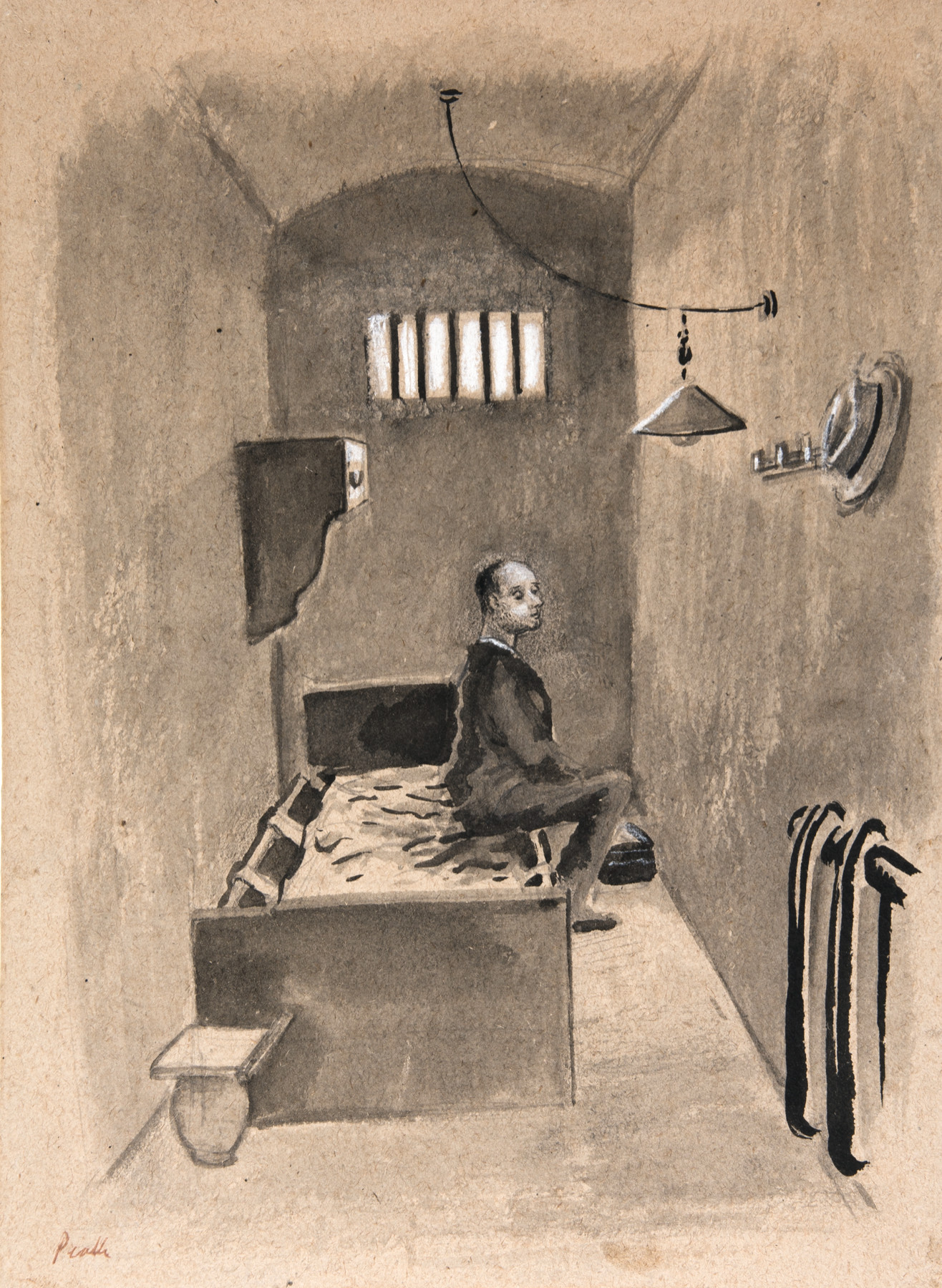

In 1945, Mervyn Peake offered his services as a war artist to Charles Fenby, the editor of Leader, a weekly current affairs

magazine. Fenby agreed that he could go to Germany to make drawings. However, as Peake was not recognised in Fleet Street as a writer but only as an artist, Fenby asked the journalist, Tom Pocock, to accompany him. Pocock would later recall their tour in 1945: The Dawn Came Up Like Thunder (London: Collins, 1983), including their attendance of the first war crimes trial in Germany, at Ahrweiler, and their visit to Peter Back, one of the accused, in a prison at Rheinbeck in the Rhineland. As Peake wrote in a letter to his wife, Maeve, his intention was ‘to make records of what humanity suffered through war’ (quoted in Pocock 1983, page 128). He was therefore reluctant to draw Peter Back in his cell, and did so only at the urging of public relations officers. Pocock remembers that, ‘Mervyn suggested to the interpreter that Back should sit ... and he did so, while the sketching was done as quickly as the pencil could move. We left in a few minutes, the doomed man thanking us’ (op cit, page 134). The story of Back’s crime was reported in Life magazine, as can be read here:

‘[On 15 August 1944], an American Liberator began to smoke ... over the Rhineland village of Preist. Three Americans bailed out. One American landed in a tree in a wheat field. Two German soldiers started to help him out of his parachute when a crowd, headed by a paralytic much resembling Goebbels himself, tore into the wheat field. The paralytic was the Nazi leader of Preist, and he had clearly in mind Goebbels’ pronouncement, “It is far too much for us to ask that we call on German police to protect these murderers from the fate they deserve.” Goebbels was referring to US airmen, described in the Nazi press as “Air Huns” and “pleasure murderers.” The little man, one Peter Back, shot the American twice. Twice the American stood up again and came on. Another German, [Peter] Kohn, clubbed the wounded man and he fell on his face. A third, [Matthias] Gierens, swung a stone hammer into his head. A fourth, [Matthias] Krein, whose home-guard responsibility was to guard prisoners, stood by. The airman did not rise again. His body has been found but not identified. One old German, a veteran of World War I, had protested, “This man is a prisoner: this is no way to treat him.” Peter Back sneered, “You can bury him and put forget-me-nots on his grave.”

The trial of three men, not including Peter Back, was held in Ahrweiler [on 1 June] by a military commission named by Lieut General Gerow of the Fifteenth Army. The prosecution cited the Ten Commandments, the laws of decency, the Laws and Customs of War and Nazi German regulations for the treatment of prisoners. All three were sentenced to death by hanging, but General Gerow commuted Krein’s sentence to life imprisonment. Back was caught [on 6 June] and sentenced [16 June]. [He was hanged on 29 June.]’

(Life, 16 July 1945, Page 17, ‘US Army Justice Falls on Germans’)

FRAMED